Color in Printing

We want to give you a better understanding of how color works in a professional print environment so you’ll consistently achieve accurate, high quality work. There is a lot to learn about color space, color theory, and how different printing techniques can change how to use color in your print projects.

What Is RGB Color?

RGB (red, green, and blue) is a model based on light energy. It’s what’s called an “additive model,” meaning adding the highest strength of all the colors of light together will give you white. If your laptop or device were suddenly shut off, your screen would immediately become black because no light would be passing through it. Speaking of computers, RGB is the color space most commonly used to display colors on a computer monitor. That means it is the color space you likely used to build your designs.

How is CMYK different from RGB?

CMYK is a subtractive, pigment-based model. Instead of starting with black, we start with white (like white paper) and the color subtracts from the amount of white you start off seeing. In CMYK printing, there are four color different plates, each printing a different color of ink: cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. These colors mix together to remove color from white light, producing the image you see.

While the first three letters, C, M, and Y refer to the first letter of the ink/plate they represent, the letter K refers to the black plate and represents the first letter of the word “key.” Black establishes a frame of reference by “keying” all of the colors so that your eyes can interpret a color image.

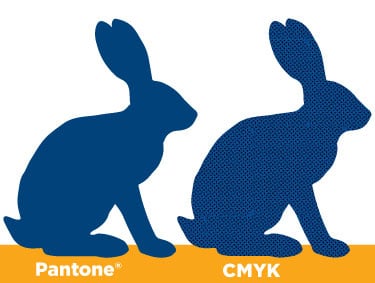

So how do the cyan, magenta, yellow, and black inks produce such a wide range of colors using just four inks? The colors are printed in varying percentages using something called a halftone dot. If you look at any printed piece with a magnifying glass, you’ll be able to see the halftone dots that make up the artwork.

Further Reading: RGB vs. CMYK, and Converting Your Colors

The number of colors of light you can see far surpass the number of unique colors you can get by adding four different pigment inks together. That means that the “gamut,” or range, of colors in the RGB (light-based, additive) spectrum far exceeds the gamut of the CMYK color space. In fact, some colors in the RGB model will never be achieved with CMYK printing colors alone.

A gamut describes the number of colors and tonal range that a specific device or environment can show you. Then certain colors cannot be produced on/by a device, those colors are said to be “out of gamut.”

Further Reading: Designing for Commercial Printing

Spot colors

There are times when we really need to see a specific color in print, even when it can’t be achieved by combining cyan, magenta, yellow, and black inks. Some brand standards, for example, specify very exact colors for their business identities and collateral. Maybe you want to increase the perceived value of your printed piece. Maybe you’ve designed a high-profile brochure or annual report that needs a little something “extra” – like a spot metallic ink – to give it a luxurious feel.

If you try to print them in CMYK, a lot of vibrant colors like bright orange and neon green come out looking kind of funny (and definitely not what you intended). Navy blue comes out looking more purple and grey. Silver looks sort of grey, and gold really just looks brown.

These specific colors can be printed even if they’re out of gamut, but they must be printed with solid or “spot” colors instead of with process inks. With spot colors, the inks are usually printed in solid, single-color blocks instead of in layers using the traditional CMYK mosaic-like dot pattern. On occasion, they also get overlaid translucently on top of a CMYK base in order to extend the available range of CMYK pigment mixes.

The Pantone color library is the industry standard library of spot colors. Their reputation grew based on the variety of multi-pigment specialty inks they offer and the legendary color-consistency of their inks. Before going crazy on adding spot colors to your pieces, though, keep in mind that these colors will significantly increase the cost of any print job since the press must be completely cleaned both before and after printing with these inks to avoid any color contamination and guarantee color accuracy. The prices of spot color inks can also vary based on which specific pigments and colorants go into a certain color (metallic inks tend to be on the higher end of the cost spectrum).

Further Reading: Pantone, RGB, and CMYK

Note: While spot colors can be fun to play with in your image editing and desktop publishing software, if you know that you’re never going to print actual spot colors, keep you color values as CMYK. You’ll have a more accurate visual preview on the monitor, and avoid additional delays with getting your project printed.

Color management

You want your printed piece to look as much as possible like the colors that you see on your computer monitor, right? That’s never really possible, to be honest. Why? Because digital screens can show you colors that you can’t actually print, and some colors that you can print can’t be displayed on a computer monitor.

We may not be able to achieve perfection, but we can make colors more consistent. That’s color management. Good color management gets you consistent and accurate results when you’re presenting, printing, or otherwise sharing your images.

Color workflow

The accurate reproduction of full color images and artwork requires following a careful and proven workflow. A color workflow maintains the best translation of colors from device to device or environment to environment throughout the production process, each with its own color processing standards and capabilities.

For example, you’d perhaps first have a digital camera. Then, you’d have a monitor (or multiple monitor) display. Then, you’d have the environment of your image editing software (such as Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, or Acrobat), including any specific adjustments you choose to make. You’d need to consider your paper, your printer, and the pigments available for your use. Each of these environments must be carefully managed for consistent and predictable artwork results.

Further Reading: Fix Color Issues with the Ink Manager

Why, for example, might the images on your screen differ from your final printed piece?

- Your human eye can see more colors than any combination of inks can create in print.

- Monitors typically use RGB color (additive model — adding to make white), but offset printing uses CMYK pigments (subtractive color — subtracting from the existing white).

- Printed images have less visual range, saturation, and contrast than digital images, so in print, colors will usually appear darker and less vibrant. Paper texture and brightness will also have an effect on any image, and digital displays are unable to accurately mimic those effects.

- The layering and overlapping of inks results in subtle color shifts and blends that can’t be exist in the discrete pixels of a digital image on screen.

Effective color management — including color calibration — ensures that you’ll be able to predict and work around any inconsistencies.

Color calibration

Color calibration guarantees adherence to a known set of color standards. Color standards provide a common base language or code for all devices to reference, such as the proper distribution of tones from black to white. Referring to the same code allows the translation of color representation between devices to occur seamlessly. If one of the devices in your own workflow is unable to reproduce certain colors, you’ll want to know when to make adjustments and when to accept the available output.

As the first step in your color workflow, you’ll want to calibrate your computer monitors. Your monitors are the windows through which you’ll make your biggest image editing decisions. Without an accurately color calibrated monitor, you can’t be sure that any decisions you make will produce a reliable outcome. Emitted light produces an image on a screen, whereas reflected light produces a visible image in print, so you’re going to need to bridge that gap without losing visual accuracy.

What happens if you don’t calibrate your monitor color? You lose accuracy. If your monitor isn’t showing you accurate images, then ay edits you make are just guesses. Do you really want to spend hours and hours editing your artwork, only to find out you made the wrong (or even just ineffective) tweaks? Or have your prints come out looking awful because you couldn’t really see what you were doing?

When you’re ready to calibrate, here are some basic steps that a monitor calibration tool might lead you through:

- Choose which monitor (if you have more than one) that you’re going to calibrate first.

- Adjust your white point to be slightly cool (6,500 degrees Kelvin – closer to blue), which produces a more natural-looking image on your screen compared to warmer tones. (Note: You don’t want your monitor to be overly blue, either, which is common error – your monitor shouldn’t be so blue that you feel the need to add yellow to your images to “correct” them.)

- Adjust your luminance value to 120 candelas per square meter. (Note: You don’t want your monitor to be too bright either, which is another common error.)

- Some calibration software may then begin generating and then measuring a variety of color and tonal values on the monitor. The software will then make adjustments to your monitor in order to produce the most accurate colors possible within the limitations of your hardware.

- You’ll then have the option to save this monitor “profile” and set it as your default.

- Check the “before” and “after” comparison to confirm you’re satisfied with your new settings.

- Proceed confidently with your images!

You can also buy an assortment of color calibration tools that help you calibrate display monitors. Be sure and get a calibration tool rated for print color management.

Choosing a color space for working with your images

When you’re opening a new document in your image editing or desktop publishing software, you’ll most often stick to the RGB color mode. That’s because you’ll usually be working with images in their most glorious and full color range, which only exists in the RGB color space (especially when the image was captured with a digital — meaning RGB — device in the first place).

You’d even use the RGB color mode if you wanted to work with an image in grayscale, adding adjustment layers to remove the appearance of color. You should definitely keep your image in RGB as long as you’re actively working on it, and your master file should always be RGB.

Some benefits of staying in RGB, even if you’re eventually going to print, are:

- The flexibility of using the same artwork file for producing print pieces as well as vivid, web-based graphics

- Keeping the image data for the larger RGB color gamut intact

- Access to the benefits of all the filters and adjustment layers in Adobe Photoshop (many Photoshop operations, like Filters, work in RGB but not CMYK)

- Avoiding the regrets of losing huge amounts of image data by converting to CMYK too soon

- Saving space on your hard drive (RGB images are 25% smaller than CMYK because they only have three color channels instead of four)

- Saving the time it would take to individually convert RGB images to CMYK

Within the RGB color space, there are three main options you’ll want to consider, each with a different available range of colors:

- The sRGB color space

- The Adobe RGB color space

- The ProPhoto RGB color space

(Ultimately, though, the impact each of these color spaces will have on the available color range isn’t going to have a critical impact due to the capabilities of today’s printers and monitors.)

sRGB

sRGB has the smallest color range (gamut) and is the most appropriate for images that will be displayed on a screen. It’s less than ideal for anything that will be printed because it’ll prevent the use of some colors that your printer actually could make. Many people put down the sRGB space. However, it is, in fact, the color space of the digital world, the color space of most modern monitors, and it’s even the color space of most commercial photo lab printers.

Adobe RGB

Adobe RGB tends to be the safest and most flexible option. It’s got a large color gamut, and there aren’t too many additional things to worry about. Adobe RGB is the most commonly used RGB profile in print; in fact, it’s even recommended to export files for prepress in Adobe RGB instead of in CMYK, since Adobe RGB completely encompasses both the sRGB and CMYK color spaces. This means Adobe RGB can keep the integrity of all the color possibilities that both of these spaces can produce.

ProPhoto RGB

ProPhoto RGB has the largest available color range, which even includes colors that aren’t part of the visible spectrum. You should only consider this color space if you’re working in the 16 bit per channel mode. The main benefit of the ProPhoto color space is that it keeps the data that applies to the colors your monitor can display, the colors your printer can produce, as well as all the colors that printers and monitors in the future will recognize.

If you’re using ProPhoto RGB, we recommend you maintain that color space throughout the image editing process, and then convert your image to sRGB when you’re saving it for the web or sending it to another party. If you’re both editing and printing your own images, you’ll have the most flexibility if you leave your images in ProPhoto RGB.

Assign Profile versus Convert to Profile

A color profile defines a particular device’s range of color reproduction as well as how that device stores the color information to begin with. If an image that you open doesn’t have an “embedded” color profile, this means that even though specific RGB values exist in your image, your image editing software doesn’t know what those values mean. It’s trying to interpret the information in the image but can’t figure out the appropriate translation.

If an image doesn’t have an existing profile, you will need to assign one so that the color data gets interpreted accurately. Assigning a profile means consciously choosing the way an image’s color values will be interpreted and matched with specific RGB values and visual display. You can do this pretty easily in most design software, such as Photoshop, with the Assign Profile option. When you assign a color profile, you’re intending to change the image’s appearance.

You can also convert color to specific color profile. This method assumes that an image already has an assigned color profile. This function will take note of the image’s current appearance and then convert the color information while keeping things looking the same (or as closely as possible, anyway). With Convert to Profile, you’re intending to maintain the status quo, color-wise.

If you still need to convert from RGB to CMYK

These days, it’s recommended to keep your artwork in RGB, even when you’re going to be sending it to print.

The old “RGB versus CMYK” color wars don’t matter much anymore. RGB content can now be seamlessly processed by most modern print workflows and gets converted on the fly to CMYK for any offset printing applications. Digital output devices like professional digital printers may even give you better color if you don’t convert to CMYK.

Sometimes, though, you won’t be given a choice.

Your printer may be gun shy. He or she may have been doing things a more traditional (“old school”) way for so long that they don’t realize the flexibility and ease that modern technology can create. What were once commonplace mistakes (like leaving artwork in RGB) no longer cause problems – and sometimes even work to our advantage.

A lot of old school print shops still recommend converting images to CMYK. In Adobe Photoshop, you could go to Image >Mode > CMYK color, which will convert the image to CMYK. But not only will you immediately lose irrecoverable image data, Photoshop will make this conversion based on your current color settings for the CMYK color space and is rarely, if ever, correct.

If your printer still insists on CMYK deliverables, first ask for a custom CMYK output profile. Not necessarily a profile created for your print job alone, but a print profile that they’ve found works well based on their specific ink and press configurations.

Even with a custom profile, be extremely careful when navigating this territory. Making a color mode conversion is a one-way street. Besides using your “Undo” command immediately after making the switch, you won’t be able to retrieve any vividness or color data that gets lost.

You don’t want to throw away any color information away prematurely, so one option is to keep your working files in RGB but export to a CMYK PDF. You can use a preset or printer profile that makes the conversion for you, creating a new CMYK file but leaving your native RGB file alone.

Further Reading: Choose the Best PDF Preset for Printing

To continue designing and editing with all of the features and possibilities while keeping an eventual CMYK output in mind, you can choose View > Proof Colors in Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, or InDesign. This way, you can see how your colors will look after conversion to CMYK, but all of your image data will remain intact in your original source files.

The main benefit of using “Proof Colors” is that you’ll avoid the point of no return. Your colors won’t get converted to CMYK until you actually export to a Print Ready PDF. Once you’ve exported to a Print Ready PDF and opened the file in Adobe Acrobat, you can confirm the CMYK conversion by going to Tools > Print Production > Output Preview. There, you’ll be able to see the CMYK separation plates, even though you began with an RGB image.

How are you going to print?

Today, traditional and modern printing methods coexist. You’ve got nearly unlimited options for producing your perfect printed piece. Here’s a summary of the most commonly used print processes.

- Sheet-fed offset printing. Capable of printing very crisp, detailed, high-quality pieces. Can handle heavy paper stock. Allows for true spot colors. A perfect method for producing prints of fine art or brochures, or manuals. Uses process color and spot colors.

- Web offset printing. The best for high volume print runs, especially those which may require inline finishing such as folding or gluing.

- Letterpress. An elegant and historic method of printing most often used on heavy, textured paper stock to create memorable pieces with character.

- Digital printing. An efficient method for high-quality print runs of less than 5,000 which also allows for variable data and personalized mailings. Today, digital presses are incredible advanced and are nearly indistinguishable from offset printing, but very few digital presses support true spot colors. Some inline finishing options may be available depending on the specific printer. Because they’re not just working from four plates, digital presses support the wider and more vibrant color gamut of RGB images – finally ending the RGB vs CMYK debate.

- Silkscreen. The printing method most often used for apparel, products, and a variety of irregular surfaces. A screen gets burned for each ink color in place of traditional metal plates.

Of all the common printing techniques summarized above, your biggest decision will most likely come when evaluating offset versus digital. Each year, the quality of digital printing increases. In fact, the print quality of digital can often matches that of offset (often at a lower cost). Here’s a closer look at your choices:

Offset printing

Offset printing (lithography), as previously mentioned, is most commonly associated with high-volume commercial print jobs. (Visualize large rolls of newspaper running through a very large and loud press.) This traditional method of printing has been around for over one hundred years.

For offset printing, your artwork’s colors will be separated and the separations will get burned onto four plates – one each for cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. Pantone spot colors may be substituted for any four of the colors, and additional plates may be burned if special spot colors have been requested in addition to the traditional four.

The imprinted plates transfer the artwork onto rubber rolls, which get spread with the associated inks. The inked image then gets transferred (“offset”) from the plate onto a rubber blanket. Your chosen paper stock is then fed through the rubber rolls and gradually layered with the ink on each plate to complete the printing of your final artwork as designed.

How Process Inks Are Made for Offset Printing

If you choose to go with offset printing, you might want more insight into just how these workhorse inks get made, right? The perfect printing ink would achieve high marks in number of areas (including set speed, gloss, running ability, and rub resistance), so the ink-making process is just as in-depth as you’d expect.

Printing inks are made of up two primary ingredients: pigment (the color) and a vehicle which carries the color. The pigment usually starts in powder form, and the vehicle tends to be a kind of varnish-like substance that’s sticky like honey. The vehicle components (whether thick or thin) are weighed into a pot and then added to a mixer.

The mixing process heats them together and the heat makes for a thinner consistency, which allows for the pigment to be easily incorporated in the varnish until it’s no longer a powder, but a thin liquid that can easily run through a printing press.

Next, in case any pigment particles are still stuck together, the lumps of pigment get broken apart in two different machines: a bead mill filled with tiny steel balls which roughly break the pigment particles off of the clumps, and a three roller mill which has three steel rollers moving in opposite directions. The steel rollers smears the pigment particles apart instead of knocking them about like the bead mill, and results in a glossy, smooth ink with a high color intensity.

Once a batch of ink gets to this stage, several quality control tests occur. A grind test takes place to make sure that every particle of pigment has been reduced to its smallest possible size so that it’ll print smoothly and consistently. Then, the ink is run through a “bleach test” where it’s mixed with opaque white to see how far it’s been developed. If everything looks good, the ink is moved to another mixer where waxes and dryers are added to impart necessary qualities to the ink. A final quality check on ink tack ensures that the ink is just sticky enough to adhere, but not so sticky that it gums things up.

Once that ink meets quality standards, it gets packaged via another three roller mill to remove any air bubbles and add more gloss and polish.

Offset Press Setup

- The first step before beginning any new process print job is cleaning the press. Everything used in the last job, from printing plates to cylinders to fountains and rollers, must be uninstalled and cleaned. Starting with a clean, fresh press isn’t just about preventing ink contamination; it’s also important to make sure that any dirt or leftover residue doesn’t disrupt the registration or alignment for the new job.

- The second step is creating color separations. Your composite artwork needs to be separated into four different artwork files (one each for cyan, magenta, yellow, and black), which are called color separations. Each separated file will get laser-engraved onto its very own thin metal own printing plate.

- The third step is laser-engraving the metal printing plates. Each coated thermal plate gets inserted into an imagesetter, where lasers output each plate’s image by heating areas of the plate to different degrees (the temperature varies depending on how much color ink each area should collect). The plate moves out of the laser compartment and through a cleaning solution to wash away the heated parts of the coating. The plate now contains a negative image of what will appear when printed.

- The fourth step is installing the four newly burned plates into the printing press. The plates are flexible enough to get clamped around plate cylinders inside the press, which will rotate while water and ink get added to the surface.

- The fifth step is calibrating the press. The press operator will perfect the color output by using calibration software. Output color density can be changed using levels and curves, as well as other tools. The calibration software also calculates ink absorption by taking into account the thickness of the chosen paper and any coatings being used. The operator starts the press at a slow speed to check the first prints for alignment and color. Any final adjustments get made so the press can ramp up to full production speed.

Use offset printing if:

- You need to print large quantities. Offset printing can be much more cost effective in bulk because you pay a lump sum for paper and press time (in addition to set up) instead of an unwavering, flat rate per piece. With offset, the more pieces you print, the less you’ve had to invest in each one.

- You have very specific paper stock or ink color requirements. Digital printing tends to be more restricted in these areas.

- You need consistent, reliable, perfect image quality. With offset printing, you won’t have to worry about streaks or spots or stains. Your details will be impeccably crisp and defined.

- Your color really matters. Offset printing is known for the best color balance and accuracy, especially since custom color inks can be precisely mixed for your job.

- You’re working with unique materials. Offset printing gives you more flexibility in terms of the weight and finish of your stock, as well as allowing custom-sized material.

- You’re not in a rush. You’ll need to allow a bit of time for your plates to be created and the press to be set up for your very own print run.

- You trust your editing and proofing teams completely. Once an offset print run begins, any errors (like typos) are a big deal to fix. You’ll have to start the plate and setup process all over again, and anything you’ve already printed (along with the initial setup) will be a loss.

Digital printing

Digital printers look a lot like giant versions of the printer you have in your house. They print sheets one at a time, dispensing ink on demand instead of needing to burn individual color plates. There’s a lot less mystery in the digital process, since most of us have already been using digital printers of some sort for years.

A digital press is high-end color output device, toner-based, and can print 100 pages per minute. Many digital presses can print up to 300 line screen, which is a high quality print. Some digital presses can support special-mix spot colors, but you won’t generally have access to as many Pantone colors as offset printing can accommodate. Even without exact matching, though, the colorants in digital presses can quite closely approximate special spot colors because they have access to a much wider color gamut.

Besides digital presses, inkjet devices are also powerful modern digital printing machines, and their capabilities continue to increase. We aren’t talking about the inkjet printers you have at home, these industrial presses come in large format and grand formats, both of which mean new possibilities in terms of printing surfaces and sizes. Flatbed inkjets can print on metal, glass, or plastic; product decals and window clings which used to require silkscreening can now be printed with inkjets. Inkjet UV inks even permit the printing of outdoor signage!

The wide color gamut of digital printing colorants becomes an even bigger advantage when using inkjet printers. The colorant range allows the mixes of colors beyond the offset standards of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. Unique colorants can be added to inkjets to extend the range of printable colors past traditional CMYK blends.

Because of this wide color gamut, RGB files become printable. RGB images are capable of producing a wider range of colors than CMYK images. And the wide gamut of digital toners and inks surpasses the available range that offset printing inks can render; even CMYK digital toners also have a wider gamut than the four process inks. Spot colors can be closely approximated via built-in recipe books which generate the best options for producing a near-match.

Use digital printing if:

- You need something printed, fast. Since digital printing doesn’t bother with the extensive setup required by offset printing, rush jobs are no problem.

- You need to see a final printed piece before committing to the job. It’s easy to crank out a single copy from a digital file, but it would be awfully expensive to set up an entire offset press for just a single printed sample.

- You’re printing a relatively small run. With digital printing, each printed sheet costs you the same amount of cash, so you won’t have to invest in plate and press setup when you’re just making just a few copies.

- You’re using standard materials and paper stock. Digital printing just doesn’t have the flexibility of offset printing.

- You need something personalized. Because of the “digital” nature of digital printing, you can easily import spreadsheets of values that need to be printed uniquely. This is called variable data printing. Offset printing, on the other hand, doesn’t accommodate such customization; every piece must be the same.

- You want to print multiple versions of the same piece. Because there’s no extensive setup process, you can print as many variations as you like for the same cost per piece.

- You don’t need everything to be perfectly crisp. And by perfect we mean, beyond the powers of a regular human eyeball. When printed on the best digital presses, you likely can’t tell the difference from an offset press without a microscope.

- You’re not too concerned about exact color. While offset printing gives you the control of perfect color matching, digital printing just does the best it can to match whatever colors you chose. Digital printing can blend inks, but those blends will never be as perfect nor as reliable as a custom Pantone mix.

Have you enjoyed this journey through color and print, but need some more guidance? Talk to a print expert today by calling 800-930-7978.